Program

Photo by K. Miura.

JOSEPH ACHRON: HEBREW MELODY

JOSEPH ACHRON

(born 1886 in Lozdzieje, Poland, now Lasdjaj, Lithuania; died 1943 in Hollywood, USA)

Hebrew Melody (1911)

The nigunim, which are personal, improvised tunes, were passed on by the Jews from generation to generation through the centuries. These soul-searching melodies without words poignantly re-kindled the lives of the Hasidic Jews in Eastern Europe in the early 19th and the 20th centuries. One particular kind was used in prayer and for study, and it can be assumed that Achron heard the Nigun that became the Hebrew Melody sung by his grandfather at the synagogue and at home.

Joseph Achron and his brother, Isidor, were musically trained from an early age by their father on the violin and the piano respectively. Joseph, who was considered a prodigy, gave extensive concert tours to all the cities of the Russian Empire following his debut in Warsaw at the age of seven. At the St. Petersburg Conservatory, which he entered in 1899 at the age of 13, he was a member of the violin class of the legendary teacher, Leopold Auer, along with Jascha Heifetz and Nathan Milstein.

While in St. Petersburg, Achron became active in the Society for Jewish Folk Music, which had been established to promote, organize, and present Jewish music. The impact it had on Achron is obvious: much of his compositional output makes references to the folk elements of the Jewish people.

Achron himself premiered the Hebrew Melody in 1911 in St. Petersburg as an encore after a special tribute concert to the Czar. Many violinists, including Heifetz, picked it up immediately, popularizing the work throughout the world. In addition to the natural beauty and the haunting quality of the melody, the closeness of the violin sound to the human voice and the importance of the instrument in Jewish culture made the work a perfect match for the character and the original purpose of its tune.

In 1922, Achron established a publishing company for Jewish music in Berlin. He traveled to Palestine in 1924 but stayed only a short while. With the growing unrest in the world political situation, he emigrated to the US in 1925, but found only partial refuge there. At first he settled in New York and taught at the Westchester Conservatory, while making an unsuccessful attempt to reinstate his violinistic career. In 1934, he moved to Hollywood, where he worked as a film composer. On his death in 1943, Achron’s friend, the composer Arnold Schönberg, described him in an obituary as the “most underrated modern composer.”

Notes © 2003 by Midori, OFFICE GOTO Co.Ltd.

Referential sources available on request.

JOHN ADAMS: ROAD MOVIES

JOHN ADAMS

(born 1947 in Massachusetts)

Road Movies (1995)

I. Relaxed Groove

II. Meditative

III. 40% Swing

The American composer John Adams has long been recognized as a leading light of his generation. His most prominent works have often featured incendiary historical and cultural elements, frequently provoking political and social controversy. Still, it is his musical excellence that keeps Adams on the forefront of the contemporary music scene, his compositions exciting aficionados of the new, while finding popularity with a wide range of music lovers.

Amongst many symphonic, operatic and large-scale works, Road Movies, commissioned by the Library of Congress and premiered at the Kennedy Center (by the violinist Robin Lorentz and pianist Vicky Ray) in 1995, is still something of a rarity in the Adams oeuvre. After earlier compositions in a “minimalist” style, employing a strict pulse while stressing harmonic progression, Adams discovered a personal gateway into deliberately melodic writing in the early 1990s, an approach he felt more suited to composing for chamber groupings. Nevertheless, his chamber works strike us as quintessential John Adams, the more lyrical passages rich in sentiment and hauntingly beautiful, setting off music of remarkable wit, that spins, sways, croons and jives.

Adams refers to Road Movies as “travel music,” and in fact the composition brings to mind an American road trip, much as that kind of experience has been conveyed in so many classic films. The first and third movements both proceed in essentially perpetual motion, each utilizing a rocking, or a swinging rhythm, illustrating the beat of driving on the open road. Adams’s distinctive minimalist techniques are in evidence throughout the work, as he delights in repeating specific rhythms over and over. It must be noted, though, that Adams throws in “tricks,” little gestures that grind his music’s gears, to enliven the musical journey by momentarily thwarting his listeners’ expectations.

The first movement develops in a layering pattern, building upon an initial picture with new, repeating fragments manipulated to create an increasingly dense overall statement. Off-rhythms within the larger regulated tempo have a humorous, rather than confusing, effect. The irregularities in this music do not come from complex meter changes, but instead are crafted to be on and off beats in a rather asymmetrical pattern.

In the second movement, the mood turns contemplative, in the style of the blues. The violin’s lowest string, the G, is tuned a whole step lower to make it an F pitch. Since the tonality centers on the G-key in this movement, the F is a 7th pitch going upwards from G (or in reverse a step below the G). This focus on the 7th pitch is a typical characteristic of the blues, and is specifically known as the “Blues 7th”. The lowered G string creates a looser kind of sonority for the instrument, giving the movement a sense of languid nonchalance. This quiet attitude is in clear contrast to the two outer movements, which are defined by rhythmic jauntiness and percussive articulation.

The title of the final movement, 40% Swing, refers to the computer setting on a MIDI. The violin and piano swing side-by-side, sometimes in full concert with each other, at other times more independently. Adams describes the third movement as “for four-wheel drives only” and the listener just needs to hang on for this wild ride. Ever so intense for the players, the movement giggles all the way to the end.

(April 2008/rev. July 2014)

Notes © 2008 by Midori, OFFICE GOTO Co.Ltd.

Referential sources available on request.

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH: SONATA NO. 2 IN A MINOR BWV 1003

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH

(born 1685 in Eisenach; died 1750 in Leipzig)

Sonata No. 2 in A minor for Solo Violin BWV1003 (1720) from the Sei Sonatas e Partitas senza basso

1. Grave

2. Fuga

3. Andante

4. Allegro

Johann Sebastian Bach’s music needs no introduction. But for such a famous and distinguished composer, surprisingly little is commonly known about his personal life except that he had two wives, 20 children and was a devout Lutheran who held several long-term positions, both inside and outside the church. His music is universally respected; his works epitomize music as an international language.

After Bach’s death in 1750, his music was neglected for nearly a hundred years and the few people who knew about him thought of him as an organist rather than as a composer. The rediscovery of Bach began with the publication of a biography in 1802 by the German musicologist Johann Nikolaus Forkel, who wrote that “This sublime genius, this prince of musicians… dwarfs all others from the heights of superiority.” Then in 1829, the young Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy conducted a performance in Berlin of the St. Matthew Passion, which had never been heard outside Bach’s own Leipzig church. A performance of the St. John Passion followed in 1833. Camille Saint-Saëns, among other composers, made transcriptions of Bach’s works, drawing them to the attention of a wider public. In 1850, a complete critical edition of Bach’s works was undertaken; it took 50 years to complete.

Bach wrote Sei Sonatas e Partitas senza basso (Six Sonatas and Partitas without bass) for solo violin in 1720 during the six-year period in which he was employed by Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cothen. While at Cothen, which was a secular court, Bach was released from the many liturgical duties that had been required of him in his previous employment. Most of the music he wrote in Cothen was therefore secular and instrumental. The Brandenburg Concertos, the Well-Tempered Clavier and the Six Suites for Cello also date from this period.

Like the rest of Bach’s compositions, the Six Sonatas and Partitas were forgotten after his death. Their revival began with the violinist Ferdinand David, who prepared the complete set for publication in 1843. Joseph Joachim also performed selected movements, helping to make the works more familiar. Felix Mendelssohn issued the Chaconne movement of the D minor Partita with an original piano accompaniment and Robert Schumann issued all six sonatas and partitas with piano accompaniment in 1854. Brahms and Busoni later made piano arrangements of the Chaconne. Nevertheless, it was only in the 20th century that the six works took their rightful place among the masterpieces of the violin repertoire. The Six Sonatas and Partitas (actually three sonatas and three Partitas), are the pinnacle of the violin repertoire because of their complexity and their beauty. Emotionally powerful and passionately involving, these pieces challenge the performer to the limit of his or her technique and musical integrity. Many violinists feel that a lifetime is not long enough to master these great works.

Adjustments have often been made to the modern violin to increase the tension of the strings in relation to different parts of the instrument so as to maximize the sound volume to meet the demands of large concert hall settings. During Bach’s lifetime, violins had shorter fingerboards and lower bridges; thus playing double and triple notes was less difficult than the same execution on modern-day adjusted instruments. Bach’s works demonstrate complete mastery of contrapuntal writing, which requires many voices to be played simultaneously while often retaining the independence of the lines. For example, in the Fugues of the six sonatas (Bach followed the slow-fast-slow-fast movement structure for all three sonatas with the second movement being a four-voice fugue), the various lines interact, and should be played as if by separate violinists.

The Sonata No. 2 in A minor begins solemnly with the Grave movement. In this somber opening, the melodic lines are lyrical yet highly ornamented, and contain unusually large intervals for Baroque music–certainly the widest leaps of the first movements of the three sonatas. The last two and a half bars serve as a bridge to the next movement, the Fuga (Fugue). The first nine notes of the four-voice fugue are the rhythmic basis for the entire movement, each voice in turn taking a leadership role. There is no noticeable break in this long movement; the music continually heightens in intensity until the climax at the very end.

The third movement, Andante, resembles a procession. The two voices take distinct roles, which they maintain through the entire movement: one is an aria-like melody; the other is strict, ostinato-like eighth-notes. The quiet sound of the final broken chord fades away into the abandon of the fast Allegro final movement. Here, the composer specifically indicates the dynamics forte and piano, as well as bowings that enhance the legato and articulated execution of the notes. The 32nd notes throughout add direction and flair, manipulating the momentum of flow with pleasing surprises.

(May 2005)

Notes © 2005 by Midori, OFFICE GOTO Co.Ltd.

Referential sources available on request.

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH: SONATA NO. 3 IN C MAJOR BWV 1005

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH

(born 1685 in Eisenach; died 1750 in Leipzig)

Sonata No.3 in C Major for Solo Violin, BWV 1005 (1720)

1. Adagio

2. Fuga

3. Largo

4. Allegro assai

Johann Sebastian Bach composed six solo works for violin in 1720, while he was serving in the court of Prince Leopold of Cöthen. This set of sonatas and partitas is considered by violinists to be at the pinnacle of solo literature for the instrument. Certainly no other work poses such a challenge to the player for its technical, intellectual, and artistic integrity. Any one of these sonatas or partitas can be considered as a base for all musical endeavors that follow.

Around the time he wrote these masterworks, Bach was fully enjoying working in a secular court. He was freed from the daily ration of writing Cantatas, as well as Masses and other choral works, and from other musical (non-composing) responsibilities. In Cöthen he was able to experiment with a new creative vigor, and his employer clearly encouraged him in this direction. Thus, a great list of secular instrumental compositions dates from his six years there, including the Brandenburg Concertos, the Cello Suites, and the Well-Tempered Clavier.

The six Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin consist of three sonatas and three partitas. The Sonatas are in four movements, following the slow-fast-slow-fast order, a form known as sonata de chiesa (“church sonata”) with the second movement being a fugue in four voices. In a fugue, a theme (‘part’ or ‘voice’) is played and extended or developed through imitation. The three Partitas are mostly a collection of Baroque dance movements – they are not exactly meant to be danced to, but they take the rhythm and inspiration from the dances, in the usual tradition of a Baroque partita.

The opening movement (Adagio) of the C Major Sonata (No. 3) begins solemnly, played on a single string for an entire bar, already distinguishing it from the other two sonatas, which both start with a four-note chord. Bach then puts one new voice at every measure, and each addition produces a richer texture. Moreover, again in great contrast to the other sonatas of the set, the most distinguishable character is not in the melodic line given to one voice with other lines accompanying or elaborating in harmony, but in the recurring rhythm of a dotted 8th followed by a 16th (ta-a-a-ta). In fact this rhythm, found three times within a measure, is the consistent force in the entire movement, making it ponderous and grave.

In the second movement (Fuga), the clarity of the individual lines can be heard as well as the complexities of the musical structure and textures, and therefore it serves as a testament to the player’s achievements. Elegantly proud in its character, this Fugue is glorious for its masterful skills of compositional technique and for the completeness of its craftsmanship.

The grand scale of the second movement makes the reflective quality of the following movement (Largo) more compelling and powerful. Often, the voices seem to have an on-going relationship. At times, they are more conversational, at other times, like a ricochet or an after-thought reverberance.

The final movement (Allegro assai) is imbued with a bubbly quality. Amidst the cheerfulness there is also much humor. Sparkling and full of life, this movement finally gives the player a straightforward challenge at virtuosity.

It is unfathomable for any musician or music lover today not to have been touched by the music of J.S. Bach. However, it is of interest that most of Bach’s music was virtually forgotten for about a century after his death, until the great revival initiated by Felix Mendelssohn in the 1800s. He, together with Ferdinand David, the concertmaster of Mendelssohn’s Gewandhaus Orchestra, supported performances of Bach’s music which brought great and increasing interest in them. Certainly, today one cannot think of music without the presence of Bach, and each hearing is a new experience.

(October 2006)

Notes © 2006 by Midori, OFFICE GOTO Co.Ltd.

Referential sources available on request.

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH: SONATA IN A MAJOR BWV 1015

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH

(born 1685 in Eisenach; died 1750 in Leipzig)

Sonata in A Major for Violin and Keyboard BWV1015

1. Dolce

2. Allegro

3. Andante un poco

4. Presto

The Bach family was full of musicians who served churches, courts, and towns between the 16th and the 19th centuries. Johann Sebastian was the greatest of them all. During his lifetime, he was particularly known for his talent as a performer; however, it is as a composer that we know him best today. Certainly he is considered one of the greatest composers of all time. His music is loved, learned, analyzed, and performed by both professional and amateur musicians alike.

From 1717 to 1723, J. S. Bach served Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cothen as Kapellmeister and it was during this tenure that he composed the majority of his works for the violin. These include the two concerti, the Six Sonatas and Partitas for Violin Solo, and a set of Six Sonatas for Violin and Keyboard, of which the A Major is the second.

The work is in the typical Baroque sonata form known as the Sonata di chiesa consisting of four movements: slow, fast, slow, fast. However, Bach introduces a technique that deviates from the tradition of his time-the keyboard and the violin share the melodic line. In previous Baroque sonatas, such as those by Handel, only the solo instrument presented the main line while accompanied by two subordinate lines played either by the keyboard (harpsichord at the time and frequently a piano today) and the Viola da Gamba or by the keyboard alone. The lowest line of the subordinate lines, the basso, was usually simply written as a note paired with a column of numbers that specified the types of pitches that should also be added to the musical surface. Taking the information as guidelines, the performers realized the basso freely, adding the suggested pieces and embellishing the accompaniment with trills, appoggiaturas, etc. In other words, the composer only provided a skeletal structure of the harmonic progression on the written music and left it up to each performer to flesh out the harmonies and improvise embellishments.

This was not the case with Bach’s Six Sonatas for Violin and Keyboard, where the composer wrote out every line concretely leaving very little space for the performers to improvise. The result was therefore not a solo violin line accompanied by a keyboard line but rather a work in which each line could be distinctly heard and enjoyed. Such technique gives insight to the future of the sonata form. In the classical period, namely the time of Mozart and Haydn, it was the keyboard that dominated the violin, and later on, the roles were more evened out, placing equal emphasis on both instruments.

The A Major Sonata as a whole is serious and noble in character. Perhaps because of the three important lines, rather than one accompanied by two, in even the quietest moments there is a certain degree of richness provided by the complexities. It is wonderful to be able to hear the theme in three voices played as if in canon or fugue, and one can only appreciate the genius of Bach for his extraordinary craftsmanship. However, it is the passionate empowerment—something not usually associated with the music of the Baroque period—that reigns throughout, leaving those touched by it grateful for the gift of Bach’s music.

Notes © 2003 by Midori, OFFICE GOTO Co.Ltd.

Referential sources available on request.

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH: SONATA IN E MAJOR FOR VIOLIN AND KEYBOARD BWV 1016

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH

(born 1685 in Eisenach; died 1750 in Leipzig)

Sonata in E Major for Violin and Keyboard BWV1016

- Adagio

- Allegro

- Adagio ma non tanto

- Allegro

The great masterworks of Johann Sebastian Bach are at the very core of western classical music, defining and inspiring an immortal tradition to the present day. It is truly inspiring that this man wrote music constantly and consistently, whether for the church or for secular employers, his music forever speaking across cultures and generations. Bach was largely forgotten for almost a century after his death, until his music was re-introduced by none other than Mendelssohn. For all Bach’s supreme brilliance, any number of his compositions have sadly been lost. In a sense, Bach was a victim of his times. His music was not widely circulated; he generally wrote for his employers without much regard for anything so worldly as marketing or publicity. Yet his music addresses the human soul in miraculous ways, giving hope and depth to the lives that each of us leads.

Bach’s output of violin music comes mainly from his Anhalt-Köthen years, when he was employed in a secularly focused court where he was relieved of the constant need to write the numerous cantatas and other church-serving compositions that defined his responsibilities in other postings. Much of his non-religious music stems from this period, including the Solo Sonatas and Partitas for Violin, the Cello Suites, the Brandenburg Concertos, and the Well-Tempered Clavier. Compared to the Solo Sonatas and Partitas, the six Sonatas for Violin and Keyboard register somewhat less in modern-day consciousness. However, this is not to say that they are inferior – it is more that the solo works are so monumental in impact that they overshadow most everything else composed for the violin. With these violin/keyboard sonatas, we recognize Bach’s incredible break from the trio sonata tradition, how he wrote amazingly for both instruments, with complex parts that are mutually independent yet intertwining. These works travel far beyond the convention of a main line accompanied by a figured bass on da gamba and a keyboard.

The Sonata in E Major, BWV 1016, is the third in the set of six. Like all others in the set, the sonata follows a sonata da chiesa format, of slow-fast (fugue)-slow-fast structure. The first movement is highly decorative, at the same time featuring lyrical writing for the violin. Its rich sonority lends depth to the texture, while imparting a sense of both freshness and hopefulness. The fugue that follows is a particularly delightful movement, full of elegant gaiety. The various voices interact and exchange among each other, and the manner in which the music builds and spins upon itself, fulfilling the requirements of a good fugue, is both amazing and engaging. The jolliness of expression of the second movement cedes to a somber and deeply romantic third movement, a passacaglia. While of brief duration, it is the one of the most memorable movements in the entire set. The closing Toccata provides an exciting conclusion for the sonata. This is festive music, fast notes running throughout the movement; with 16th notes in the outer sections and triplets in a middle section defined by its sense of poise, sandwiched between so much splendor.

Notes © 2016 by Midori, OFFICE GOTO Co. Ltd.

Referential sources available on request.

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH: SONATA IN E MINOR FOR VIOLIN AND BASSO CONTINUO BWV 1023

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH

(born 1685 in Eisenach, Germany; died 1750 in Leipzig)

Sonata in E minor for Violin and Basso Continuo BWV 1023

J.S. Bach left us an incredible number of great works, chamber music and orchestral, church music and secular. In truth, he was so prolific that it is difficult to determine exactly how much music he actually did write, whether some of his work has been lost, and how best to catalogue his vast list of compositions. This is especially complicated as Bach, in his various work postings, was responsible for creating music for myriad performances in church and otherwise, and often repurposed compositions, or elements of compositions, for new situations. From any perspective, Bach’s music represents a simply miraculous flow of creativity from a single person.

Bach wrote widely for the violin. Most notable are the sonatas and partitas for solo violin, the two-violin “double” concerto, two violin concertos, as well as the six accompanied sonatas. Beside these, there are other works that prominently feature the violin, including some of the concerti grossi. While Bach’s accompanied sonatas, BWV 1014-1019, were scored for violin and cembalo obbligato, this work, the Sonata in E minor for Violin and Basso Continuo BWV 1023, was originally written for violin and continuo, and an optional gamba, doubling the bass line. The sonata is thought to have been composed in the same approximate era as Bach’s solo violin sonatas and partitas and the six suites for cello, in the early years of the 18th Century. Bach was just starting his career at that time and, since his first positions tended to be in secular situations, the young Kapellmeister was left with much time to compose instrumental works.

The sonata is emotionally intricate and gripping. The violin is dominant throughout and the continuo part (most often played by a keyboard, either a harpsichord or piano, with or without the accompanying bass part,) consists, in its original edition, of a simple bass line, which needs to be expanded upon, embellished, and harmonized at the discretion of the keyboardist, as was customary during Bach’s period. (Today’s keyboard player may choose to utilize modern editions of the score for inspiration and ideas.)

The work opens with a violin-dominant section in the virtuosic mode of a toccata. Grand in its mood, though brilliant, it is not dissimilar to the Preludio of the E Major Partita BWV 1006 in its non-stop, ongoing 16th notes that seem to go climbing up and down. This movement segues directly into an Adagio ma non tanto. A tri-meter movement, the character is evocatively poignant and somber yet flowing and elegant. The two movements that follow and complete the work are both dance-inspired, an Allemande and a Gigue. These are binary in form, which is to say in two related sections that are both repeated. The Allemande was one of the most popular dances in the Baroque and Renaissance eras and, in this particular case, it is poised and stately. The final Gigue is lively – although spirited, not exactly jolly.

(October 2015)

Notes © 2015 by Midori, OFFICE GOTO Co.Ltd.

Referential sources available on request

BÉLA BARTÓK: SONATA FOR VIOLIN SOLO SZ. 117, BB124

BÉLA BARTÓK

(born 1881 in Nagyszentmikós, Hungary; died 1945 in New York)

Sonata for Violin Solo Sz. 117, BB124 (1944)

Béla Bartók’s final years, spent in the United States toward the end of the Second World War, were anything but glorious. The composer had been forced from Hungary, his beloved homeland, to avoid the Nazis, whom he had long opposed, only to experience a fraught American exile, undermined by financial frailty and the leukemia that would eventually end his life. Not quite the final years one might have expected for a composer who ranks amongst the greatest of the twentieth century, if not of all time. He was a true giant, a true Romantic to succeed Brahms.

Bartók was a precocious musical talent, who started piano lessons at an early age. In young adulthood, with his friend Zoltán Kodály, he travelled into the native countryside to research folk music of the different ethnic groups of Central and Eastern Europe. That education served as a pivotal inspiration, the folk music he learned and catalogued becoming a strong presence in all of Bartók’s mature compositions.

The Solo Violin Sonata is one of the final pieces that Bartók completed before his death in 1945. It was commissioned and premiered at New York’s Carnegie Hall by the late Yehudi Menuhin. Bartók had heard Menuhin about a year earlier in another Carnegie Hall recital in which Menuhin had performed Bartók’s First Sonata for Violin and Piano as well as Bach’s Third Sonata for Solo Violin in C Major. Menuhin had consulted with the composer in preparation for that earlier performance, initiating a dialogue that led to the violinist commissioning the subsequent sonata.

In composing his solo sonata, Bartók was clearly influenced by the solo violin sonatas and partitas of Bach, from the titles of two of the movements, Tempo di ciaccona and Fuga, to the multiplicity of voices throughout the work, and the music’s loose adherence to the Sonata di Chiesa‘s slow-fast-slow-fast structure.

The opening movement of the sonata is marked Tempo di ciaccona, and this movement is sometimes performed as a stand-alone, without the other three movements. The title does not mean that it is a chaconne; rather it is in the tempo of one. Additionally, the beat emphasis is often on the second beat of the ¾ meter, which also seems to bear some connection to the structure of a Chaconne. However, the movement’s compositional structure actually follows a basic sonata-allegro form. Always emotionally gripping, haunting at times, dramatic, bold, larger than life, heart wrenching and heart-warming, the movement presents a great challenge for its player.

The sonata’s “Hungarian” flavour, its biting rhythm and character, is present throughout. The music asks for considerable imagination from the violinist, plus confidence in his or her technical abilities – otherwise Bartók’s boldness and range of expression cannot be expressed. The violinist must have incredibly well coordinated and trained hands to maneuver through chords that require stretching of muscles and precise timing of the movements of the arm. Late in life, Bartók seems to have returned to Bach and the glories of polyphony, and when a player has the capacity to reach this music’s deep and complex emotional core, this sonata has great musical wisdom to impart.

(October 2015)

Notes© 2015 by Midori, OFFICE GOTO Co. Ltd.

(Referential sources available on request)

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN: SONATA IN D MAJOR OP. 12 NO. 1

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN

(born 1770 in Bonn; died 1827 in Vienna)

Sonata for Piano and Violin in D Major, Op. 12 No. 1 (1797/98)

1. Allegro con brio

2. Tema con variazioni (Andante con moto)

3. Rondo: Allegro

Beethoven wrote ten sonatas for piano and violin between 1797 and 1813. Both Mozart and Haydn had previously written sets of sonatas for the two instruments conceived from a pianistic point of view, placing less importance on the violin part than on its partner, the piano. Beethoven followed suit, except that in his sonatas, the violin clearly does not submit to the piano. In so doing, he broke with the tradition of the time.

Nonetheless, the piano does play a crucial role in all ten of Beethoven’s piano-violin sonatas. Himself an accomplished pianist, he continuously sought a new level of virtuosity, at a time when the instrument was also being modified to meet this. As a result, a modern violinist must be aware of the particular pianistic sounds, colors, and articulations conceived by Beethoven for the piano of his time. Thus, the piano part is an essential guide for the violinist’s interpretation of the piece. Often the sense of resistance and achievement, so characteristically inherent in his music, must be communicated to the listener.

The Sonata No. 1 in D Major for Piano and Violin is dedicated to one of his teachers, Antonio Salieri. Beethoven had initially gone to Vienna in 1792 to study with Haydn, but that relationship did not last long, partly due to the elder composer’s heavy traveling schedule and the younger’s difficult and unrefined personality. Consequently, Beethoven went on to study with others in Vienna, including Johann Georg Albrechtsberger and Antonio Salieri.

Although Beethoven’s formal instruction from Haydn was short-lived, he was still inspired by the older composer to write his first symphony and the quartets. Haydn’s Sonatas for Piano and Violin could also have played a role in encouraging Beethoven to take up the task. Added to that influence was most likely the pressure of Karl Amanda, a violinist from Courland, the present-day Latvia, whom Beethoven had befriended.

The Sonata No. 1 in D Major, Op. 12, No. 1 is a three-movement work. Written in 1797/98, it is generally joyous, spirited, and exuberant despite the fact that, by then, Beethoven was already experiencing extreme fluctuation of moods, pathological and psychotic in nature, as well as the first signs of his impending deafness. The movement indications are as follows: Allegro con brio, Andante con moto, and Allegro.

The work opens boldly in unison (both the piano and the violin playing the same material simultaneously), quickly feeding into a songful tune, first played by the violin then by the piano. Soon, the running notes and the tenser harmonies come in more frequent succession, with the two parts displayed as if engaged in a conversation, giving the sense of approaching excitement. But, humorously, Beethoven halts the forward motion, and the next section starts with the piano playing a somewhat calmer melody, eventually leading to a regal set of chords, perhaps a hint of his fascination with the military, followed by exuberant 16th notes. The next part, quite unusually for a middle section of a movement, is in a different key signature, that of F major, which starts off in piano dynamic, with the chords that were previously heard, suggestive of a military march. This section is not long, and the music returns triumphantly to that of the opening of the work, and the movement continues almost likewise.

The second movement is a set of four variations on a theme in A major. The theme has two subjects: each is first introduced by the piano and accompanied by the violin and immediately following, the roles are reversed. The first variation is entirely by the piano accompanied by the violin. In the second variation, the leadership is exchanged, with the violin playing the melody line over the piano. The next variation returns to a balanced split between the instruments, but here the entire variation is in the key of A minor. The final variation returns to the major key mode, and gives a sense of attainment.

Allegro, the last movement, is a rondo in 6/8 time. The feeling is gay and the theme incorporates offbeat sforzandos and slightly syncopated characteristics that were to become more prominent in Beethoven’s later works. The middle section, as in the first movement, is in F major. Throughout, the piano and the violin exchange roles, but never losing the dance-like quality filled with happiness.

(March 2003)

Notes © 2003 by Midori, OFFICE GOTO Co.Ltd.

Referential sources available on request.

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN: SONATA IN A MAJOR OP. 12 NO. 2

LUDWIG van BEETHOVEN

(born 1770 in Bonn; died 1827 in Vienna)

Sonata for Piano and Violin in A Major, Op. 12, No. 2 (1797/98)

1. Allegro vivace

2. Andante, più tosto allegretto

3. Allegro piacevole

Beethoven wrote three sonatas for piano and violin in A major. The best-known is the “Kreutzer” Sonata, composed in 1802, which is so massive that it functions more like a concerto or a contest for the two instruments. In great contrast, the Sonata in A Major, Op.12, No.2, written earlier, is light and delicate with the dynamic between the two instruments that of an intertwined partnership.

The three Sonatas Op. 12 were dedicated to Antonio Salieri, one of the most influential and powerful musical personalities of the time and one of Beethoven’s teachers. They are all still under the obvious influence of Haydn and have a continual feeling of lighter touch, particularly Op. 12/1. Beethoven’s trademarks of subito (sudden) pianoand stormy forte or fortissimo passages are presented in a modest way here. They do not yet have the “shocking” impact that they have in the later sonatas.

The first movement, Allegro vivace, begins without complication; the harmonies are direct and simple, and a fun-loving character is maintained throughout. The two instruments take turns in stating the themes in a conversational manner.

The key of A minor, rather than A Major, begins the lyrical middle movement. The sonority of the first Andante theme clearly resembles that of the fortepiano. As an instrument, the fortepiano has much less vibration, or resonance, and volume than the modern piano, so its sound is both sharper and softer. Moreover, of interest in the opening theme is that when the violin enters, after the initial melody stated by the piano, it does so an octave higher than the piano. This is rather unusual since the piano and violin more often play the theme in the same register in works of the same or similar genre. The second subject is richer and warmer, with a vocal-like quality. Cast in an A-B-A form, the movement returns to the beginning material and its variants, coming to a conclusion in a rather somber mood.

The Italian word piacevole (pleasant) accurately describes the final movement of this sonata. Written in Rondo form, the recognizable theme returns repeatedly throughout the movement. Beethoven does not vary it too much, but the pleasure of hearing such a beautiful tune can never bore listeners.

At the time he composed this sonata, Beethoven was already beginning to face the deafness that would eventually become profound and permanent. Yet, the immense joy and resilience in his musical output can only attest to the dignity of his person.

(March 2007)

Notes © 2007 by Midori, OFFICE GOTO Co.Ltd.

Referential sources available on request.

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN: SONATA IN E-FLAT MAJOR OP. 12 NO. 3

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN

(born 1770 in Bonn; died 1827 in Vienna)

Sonata for Piano and Violin in E-flat Major, Op. 12, No. 3 (1797/98)

1. Allegro con spirito

2. Adagio con molta espressione

3. Rondo: Allegro molto

During Beethoven’s lifetime, it was still customary for instrumental sonatas with piano to be conceptualized as a showcase for piano with an accompanying role for the other instrument. Both Mozart and Haydn, particularly in their early works, produced significant sonata sets for piano and violin that clearly gave prominence to the piano.

By the time Beethoven started to write his sonatas, the two instruments were beginning to be handled fairly evenly. Nonetheless, it must be noted that in the first printed edition of the Op. 12 set, published almost immediately upon their completion, the inscription reads “sonatas for harpsichord or piano, with a violin.”

The importance of the piano part is evident, following the tradition of the period, but one must also remember that Beethoven himself was a virtuoso pianist; his musical language is strongly keyboard-driven. Indeed, in his mid twenties, Beethoven was a rising piano star in the musical capital of Vienna. For this reason, the violin lines in all ten sonatas must be interpreted with the keyboard sound in mind.

As we know today, Beethoven’s life was filled with the tragedy of deafness, mood swings, and stormy temperament over which his genius prevailed. Certainly, one can sense evidence of this in many of his works, but the other side of his personality is also demonstrated, fun-loving and tender, with an adventuresome flair. Works such as the Opus 12 show this aspect of his character.

The E-flat Major Sonata is the third, and last, of the Opus 12 set, all composed between 1797 and 1798 and dedicated to Antonio Salieri, one of Beethoven’s teachers and an influential Kapellmeister of the Hapsburg court in Vienna. Written around the same time as the piano sonatas Nos. 4 and 7, the Opus 9 String Trios, the Opus 18 String Quartets, and the first piano concerto, the influence of Franz Josef Haydn, another of Beethoven’s teachers in Vienna, can also be heard. The general impression of the Sonata is one of youthful buoyancy that is almost addictive.

As the sonata begins, the piano takes a virtuosic leadership role; the second theme is introduced by the violin. With positive energy and mood, the music flows effortlessly, and its jolly character cannot be contained. The Adagio that follows, in C Major, is beautiful with the two instruments alternating in singing the main line. The mellifluous lines are natural and uninhibited and occasionally complemented by the bucolic rhythmic figures in the accompaniment.

The Rondo theme is catchy and gay and reminiscent of ‘Papa’ Haydn’s Hungarian panache. The two instruments are playful with each other with constant exchange of themes. Pleasing is the best way, perhaps, to describe the end of the Sonata, worthy of the twenty-minute work filled with bliss, hope, and delight.

(May 2005)

Notes © 2005 by Midori, OFFICE GOTO Co.Ltd.

Referential sources available on request.

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN: SONATA IN F MAJOR OP. 24 "SPRING"

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN

(born 1770 in Bonn; died 1827 in Vienna)

Sonata for Piano and Violin in F Major, Op. 24, “Spring” (1800-1801)

1. Allegro

2. Adagio molto espressivo

3. Scherzo: Allegro molto

4. Rondo: Allegro ma non troppo

Beethoven had a great love of nature and was particularly happy and inspired when in the forest or under the stars. The presence of God for him was reinforced by the beauty of nature. This tender side – bucolic, romantic, and gentle – contrasts with the well-known characteristics of extreme dynamic tension and emotional aura in much of Beethoven’s music, but it is indeed found throughout his oeuvre and is an important element in understanding the composer’s complex personality.

In an attempt to define Beethoven’s genius, Leonard Bernstein maintained that the composer had an ‘inexplicable ability to know what the next note had to be.’ Certainly, in listening to any of Beethoven’s works, one is aware that the composer is very conscious of what he is doing. Moreover, there is an incredible combination of sureness of musical direction and complete submission to the higher powers. Beethoven’s music is, without doubt, miraculous and godly. Therefore, it is not possible to imitate his music; it is always distinctive, uncontested, and in its own class.

The ‘Spring’ sonata, Op. 24, is the fifth of Beethoven’s ten sonatas for piano and violin. Composed between 1800 and 1801, it was dedicated, along with the Sonata in A minor Op. 23 to one of Beethoven’s most generous Viennese patrons, Count Moritz von Fries. Both sonatas were originally intended to be paired as Op. 23, Nos. 1 and 2, respectively, but through the fault of the engraver, the ‘Spring’ sonata became Opus 24.

One of the most popular of Beethoven’s sonatas for piano and violin, the work is easily remembered, even after first hearing. The music is full of joy, and its refreshing, hopeful quality makes the subtitle, ‘Spring,’ most appropriate. Throughout, the melodies are immediate, simple, and elegant. There are also humorous moments, reminding listeners that Beethoven was a master of fun and games as well.

‘Spring’ is one of only three of Beethoven’s piano and violin sonatas to be cast in four movements, the others being No. 7, Op. 30 No. 2, and No. 10, Op. 96. It opens with one of the most unforgettable melodies of all time played in F Major by the violin. The second theme which follows is more rhythmic and energetic, and the movement develops around the two contrasting themes. The slow movement in B-flat Major speaks simply and flowingly, with violin and piano alternating in presenting the theme in slightly different variations. The third movement, a scherzo and trio, is like a game of tag in which the violin and the piano bounce off each other. The coquettish impression is strengthened by the rhythmic playfulness. The finale is in rondo form, with a lyrical theme followed by three episodes. Lighthearted and spontaneous, its dotted rhythms exemplify Beethoven’s inventiveness and sense of humor.

(January 2004)

Notes © 2004 by Midori, OFFICE GOTO Co.Ltd.

Referential sources available on request.

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN: SONATA IN A MAJOR OP. 30 NO. 1

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN

(born 1770 in Bonn; died 1827 in Vienna)

Sonata in A Major, Op. 30 No. 1 (1802)

1. Allegro

2. Adagio molto espressivo

3. Allegretto con variazioni

In 1802 Beethoven spent a few months in Heiligenstadt, outside of Vienna. Despite his growing concern about his hearing impairment, which he had only disclosed to his close friends the previous year, he was fast gaining a reputation as a composer and pianist. The time spent at Heiligenstadt was an attempt to find inner calm amidst his growing mood fluctuations and fear of impending deafness, which must have discolored his approaching success. While there, he continued working on his compositions, including the Second Symphony and a handful of instrumental pieces, including the three Op. 30 sonatas for piano and violin.

The Sonata in A Major, Op. 30, No. 1 is rarely heard today in concert halls. Considered by its champions to be one of Beethoven’s most beautiful chamber works, it requires intensive listening and utmost attention to detail from the performers. Dedicated to Tsar Alexander I of Russia, it is distinctively different in character from the sudden musical outbursts for which Beethoven became so well-known.

Cast in three movements, the overall feeling is one of elegance, gentleness, tenderness, and poise. Throughout the work, both instruments share the limelight without a hint of virtuosity, and the impact of the composition is found in the intense beauty of the music. The bucolic style is much closer to, say, the Piano Sonata No. 15 Op. 28, “Pastoral,” with a hint of the gentle qualities in the last sonata for piano and violin, the Op. 96, than to the later, better-known, tempestuous A-major sonata (“Kreutzer”), which was written less than a year later. Curiously, the movement Beethoven originally conceived as a fourth movement for Sonata Op. 30, No. 1, was instead used as the final movement of the “Kreutzer” sonata. In the published version of the Op. 30, No. 1 sonata, therefore, there are three movements in all, and Beethoven has set a theme and variations as the final movement, a form he tended to use as a middle movement, but would use successfully both as stand-alone virtuosic pieces and as a final movement in this sonata, as well as in his Third Symphony (“Eroica”).

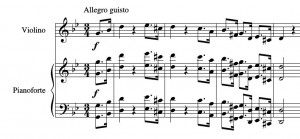

As a matter of fact, although Beethoven only specifies his last movement as conceived in a theme and variation format, the other two movements are loosely in a variation form as well, in part owing to Beethoven’s mastery of the compositional conventions: the sonata form and the rondo form. In the first movement, the idea of variation is clear in Beethoven’s infatuation with the rhythmic figure opening the sonata in the piano’s lower register. The sonata opens with a noble theme played by the piano. The rhythmic figure (see example) permeates the form; in addition to its important role at the beginning, this motive occurs at the development’s beginning and ending as the music prepares masterfully the way for this sonata’s main theme to return. The movement’s final moments also highlight the rhythm.

(Example 1: 1st Movement, Bar Numbers 1-2)

![]()

(Example 2: 1st Movement, Bar Numbers 83-87)

(Example 3: 1st Movement, Bar Numbers 247-249)

In the second movement, the combination of the rondo form, A-B-A-C-A, with the special attention Beethoven pays to creating equal roles for the violin and piano brings the technique of variation to the spotlight. In this form, the unforgettable melody introduced by the violin is repeated immediately by the piano. This pair of statements occurs twice more during the movement, separated by greatly contrasting material and saturating the musical surface to the point at which variation of the opening theme is almost required in order to keep the listener’s attention. Additionally, every important melodic utterance is stated twice, usually first by the violin and then immediately repeated in embellished form by the piano. The tradition of embellishing a repetition comes from opera, and several of this movement’s melodies resemble a simple aria from an Italian opera. Overall, Beethoven’s gift for writing lyrical melodies—a talent often forgotten in the popular “heroic” image of Beethoven—creates a movement in which tenderness is glorified, and passion is overwhelming without ever becoming abashed.

The last movement, in the form of theme and variations, provides a simple ending to an elegant sonata. It begins with the theme in the character of a refined German dance, which is followed by six variations. The final variation, Allegro, ma non tanto, does not suggest a grand finale with a dramatic climax; rather, the work concludes in an upbeat and contented mood.

Notes © 2004 by Midori, OFFICE GOTO Co.Ltd.

Referential sources available on request.

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN: SONATA IN C MINOR OP. 30 NO. 2

LUDWIG van BEETHOVEN

(born 1770 in Bonn; died 1827 in Vienna)

Sonata for Piano and Violin in C minor, Op. 30, No. 2 (1802)

1. Allegro con brio

2. Adagio cantabile

3. Scherzo

4. Finale: Allegro-Presto

During the 18th and the 19th centuries, compositional theories asserted that certain key signatures represented particular characteristics. The key signature of C minor, for example, was said to possess “tono tragico, e atto ad esprimere grandi disavventure, morti di eroi.”

This description characterizes Beethoven’s Sonata Op. 30, No. 2 in C minor. Written in 1802, the sonata can be considered the first of the monumental works for the violin-piano duo literature. Significantly, of the seven instrumental works that Beethoven was writing during the same period, the Sonata Op. 30, No. 2 and three other compositions, the Sonate Pathétique, the String Trio Op. 9, No. 3, and the Piano Concerto No. 3, all shared the key of C minor. The mood represented by this key seems suited to the inner turmoil that Beethoven must have felt as he became increasingly aware of the realities of his impending deafness.

The emotional climate for the entire piece is definitively set in the fateful opening. The impetuous momentum, the sudden turning of corners, and the tragic sonority combine with tuneful, and at times playful, sections, to create not a disarray of differences but a work of epic proportion with great power and cohesiveness.

The sonata begins with rather understated dynamics and mysterious octaves. The transparency of the sound of octaves combined with the silences of the rests only increases the intensity and sense of dread, which is followed by agitated runs and sudden outbursts. This hair-raising beginning soon gives way to a contrasting section where the theme resembles a military march.

The relationship of the two instruments is of a complementary nature, and the collaboration remains strong throughout the work. While the sound palette of the notes themselves is strongly keyboard-inspired, the importance of both parts is laid out quite evenly.

In the slow movement, Adagio cantabile, the song-like quality and the warmth of emotion is consistent and compelling. The idyllic theme, first stated by the piano, is presented by both instruments throughout the movement in new and different ways. However, even in this calmest of the sonata’s movements, there are two moments of sudden outbursts, in which ascending scales appear unexpectedly. Before the shock registers, though, the lyricism of the theme returns.

The rhythmic figure in the Scherzo that follows clearly reminds the listener of the military-inspired tune from the first movement. However, here the meter is in three, and particularly in the middle (Trio) section, the feeling of a German country dance dominates. In the outer sections, the placement of the grace notes adds humor, and wit.

In the Finale, the anguish and the fear-imbued atmosphere return. The tempo of this movement is quite fast, causing a breathless quality, and the sudden outbursts and the stops are, for that reason, even more striking. In the Coda (marked Presto), the sentiment is one of fury, and while the Sonata concludes in the tonic chord of C minor, the dominating character of uneasiness and nervousness remain beyond the final notes.

Notes © 2005 by Midori, OFFICE GOTO Co.Ltd.

Referential sources available on request.

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN: SONATA IN A MAJOR OP. 47 "KREUTZER"

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN

(born 1770 in Bonn; died 1827 in Vienna)

Sonata in A Major, Op. 47 “Kreutzer” (1803)

1. Adagio sostenuto – Presto

2. Andante con variazioni

3. Finale: presto

Beethoven had to rush to complete the writing of his Sonata in A Major, Op. 47. In truth, he practically missed the deadline, and was writing it until curtain time on the evening of its premiere in Vienna in 1803 with the composer at the piano and George Polgreen Bridgetower playing the violin. Some parts of the first two movements had to be “filled in” or improvised from the sketchy manuscript. Nevertheless this work, which on publication became known by its subtitle, “Kreutzer” Sonata, has continued to inspire great minds, such as Tolstoy’s.

Leo Tolstoy heard a performance of the “Kreutzer” Sonata in 1888, and it inspired him to complete the final version of a novella, bearing the same name. The plot of his work was based on the struggle between spiritual and bodily desires within the context of a certain marriage, and it climaxes into the husband killing his wife.

The “Kreutzer” Sonata is an extraordinary work. Performing it, I am always struck by the sheer energy and control necessary for the bursts of emotional intensity, with running notes, melodic lines, and dialogue with the piano. These qualities, combined with the extremely challenging technical demands, become mental and physical stretch exercises for the performers.

The first movement best exemplifies Beethoven’s own description on the manuscript: “Sonata for piano and violin obbligato, written in a very concertante style, brilliant (this crossed out by Beethoven in the manuscript), quasi concerto-like.” It is indeed a work in which the two instruments execute dominance, vivacity, and excitement, and in concerto proportions, yet are simultaneously heeding the delicacy of subtle chamber-collaborative sensitivities.

The introductory Adagio Sostenuto, opens with a choral-like phrase, initially by the violin and then followed by the piano. This movement is really almost entirely in a minor mode, contradicting the major key indicated in the title, Sonata in A Major, leaving the opening violin phrase the only “obvious” A major phrase of the movement. In the main body of the movement which follows, Presto, the key signature of the A major (three sharps) is now officially changed to A minor or its relative C major, which is without any sharps or flats. The beginning statement is introduced by the violin, which is somewhat interrupted by the same statement played by the piano, who completes it with a mini cadenza-like arpeggio. The movement then takes off, and although there are moments throughout hinting at calm, they are never completely so; they are, simply, suspended moments that do not settle down entirely. The end of the movement is marked by relentless fury.

The Second Movement, Andante con Variazioni, is a set with four variations, mostly in F major. Considering that this is a “slow” movement, Beethoven nonetheless incorporated much humor throughout, with his off-beats, pizzicatos, continuous trills, etc. Additionally, there are lots of 16th, 32nd, and 64th notes, generally considered “fast” notes, but in these Beethoven requires quality, utmost ease, and tranquility of execution to maintain the crystalline beauty of the movement.

The last movement, Presto, was written originally about a year before, and was to be the last movement of another piano-violin sonata – Sonata in A Major, Op. 30, No. 1. Beethoven ended up writing a set of variations for the earlier work instead, and recycled the original for use in the “Kreutzer” Sonata. After the resonating A major chord from the piano—simple, yet sustained and powerful—the violin begins, setting the mood for the entire movement. The style is that of the Tarantella, which, according to Italian folklore, was a very rapid dance intended to cure the poisonous bite of a tarantula spider. Indeed, the origin of the Tarantella was not a carefree occasion; however, Beethoven’s treatment of it is light, witty, and gay, and in noted contrast to the first movement’s stark, dramatic, tumultuous quality. The third movement is spontaneous and graceful as the two instruments dance about together, and the movement ends triumphantly with joy and aplomb.

At the time the work was premiered, Beethoven was on amicable terms with Bridgetower, who was multi-racial, a virtuoso, and was officially in the service of the Prince of Wales. However, relations between the two took a turn for the worse when both men became enamored of the same woman. Upon publication of the sonata, Beethoven, upset and furious, removed the dedication to Bridgetower and changed it to that of another virtuoso, Rudolphe Kreutzer. Kreutzer, the author of the 42 exercises infamous among violinists around the globe, did not acknowledge the dedication by ever performing the piece. Today, this work is one of the most important in the violin-piano sonata literature. Feared and loved, it is the Mount Olympus for all who perform it.

(January 2003)

Notes © 2003 by Midori, OFFICE GOTO Co.Ltd.

Referential sources available on request.

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN: SONATA IN G MAJOR OP. 96

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN

(born 1770 in Bonn; died 1827 in Vienna)

Sonata in G Major, Op. 96 (1812)

- Allegro moderato

- Adagio espressivo

- Scherzo: Allegro

- Poco allegretto

Beethoven and his genius established new standards and brought the field of classical music to a higher level. His music never fails to touch us deeply, and it reminds us to have faith in the imperfections of the human character. He has inspired films, novels, paintings, analytic scholarly works, and even a comic strip. Ironically, these manifestations–including films such as Immortal Beloved, images by Klimt and Warhol, and even the cartoon strip Peanuts–have resulted in spreading his name and his fame to new generations who may not even be familiar with his music.

As a teenager, Beethoven began to notice the extreme fluctuation of his moods. His temper and inconsistent temperament seemed to have been of a pathological nature. As early as 1796, but certainly by 1801, Beethoven also became aware of his progressing hearing problem, which moved steadily toward complete deafness. Modern medicine hypothesizes the cause of Beethoven’s deafness to be syphilis. Whether or not his impeding deafness was a decisive factor in his emotional instability, it is clear from his letters to his brothers that he suffered from psychological disorders that, from time to time, may have been psychotic in nature.

Beethoven wrote ten sonatas for piano and violin. In all of them he treats the two instruments with equal importance. Whereas the traditional works of the sonata genre from the classical period, including those by Mozart, place the violin in a subordinate position to the piano, such even-handling of the instruments by Beethoven was considered unconventional at the time, and had great impact on later composers.

Completed in 1812, Beethoven’s final sonata for piano and violin has a lyrical serenity that sets it apart from the previous nine sonatas. Dedicated to Beethoven’s devoted patron, Archduke Rudolf, it was premiered in 1812 with the Archduke at the piano and Pierre Rode on the violin.

The first movement, Allegro Moderato, opens with a fragment of three beats (a quarter note, two eighth-notes, a quarter note), played at first by the violin, and then repeated by the piano. The movement continues as each new melody grows from the previous one. The second theme reveals Beethoven’s fascination with the military.

The hymn-like second movement is marked Adagio Espressivo, and it is considered one of the most beautiful slow movements in Beethoven’s chamber music.

Performers have to breathe seemingly in slow motion to make way for the lyrical, uninterrupted line. The Scherzoin G minor follows, the only section of the piece that suggests a tremulous mood. The trio in the middle of the movement is a contrast, as it is in a major mode key of E-flat, in the style of a 3-beat dance.

The last movement, Poco Allegretto, is folk-like and is a set of loose variations, with a flowing quality similar to the first movement. In the middle of the movement is the Adagio Espressivo variation, heavily ornamented and bearing resemblance to the hymnal second movement. The theme of the movement returns after a fragmented interlude that is, surprisingly, in E-flat major. The boisterous Allegro variation quickly takes over with a barrage of 16th notes, rapidly progressing from D major to the home key of G major. This is abruptly taken over by a variation in canon, before returning at last to the home theme. The listener is surprised again with the change to poco Adagio, which is then immediately interrupted by the exciting, though short, Presto of eight bars, until the final chord of G major.

(May 2002)

Notes © 2003 by Midori, OFFICE GOTO Co.Ltd.

Referential sources available on request.

ERNEST BLOCH: POÈME MYSTIQUE

ERNEST BLOCH

(born 1880 in Geneva; died 1959 in Portland, Oregon)

Poème Mystique

Sonata No.2 for violin and piano (1924)

The Swiss-born composer Ernest Bloch was so revered in his lifetime as to be sometimes thought of as the “fourth B,” alongside Bach, Beethoven and Brahms. However today’s concertgoers seldom encounter Bloch’s work beyond his much loved, passionate piece on Jewish themes, the cello and orchestra Schelomo. That is a pity as Bloch was prolific throughout a long career, especially notable for a variety of remarkable solo and chamber compositions for the instrument of his virtuosic youth, the violin. A particular case in point is his Second Violin Sonata.

Bloch came of age in an era of incredible artistic flux, in which many revolutionary methods of compositional expression were being pioneered. He could count a group of great composers of highly diverse compositional styles as his contemporaries, including his friend, Béla Bartók, and such other giants as Maurice Ravel, Arnold Schoenberg, Igor Stravinsky, and Karol Szymanowski. Bloch borrowed, to his own ends, from all of their innovations. Many of Bloch’s own works were Hebraic in both their religious themes – though Bloch was not devout in his personal life – and in their modal writing, as derived from the traditions of the synagogue and the Jewish shtetl (village) of Eastern Europe.

Subtitled the Poème Mystique, the Sonata No.2 dates from 1924, a particularly fruitful year for Bloch, especially during a six-week sojourn in Santa Fe, New Mexico, during which he composed not merely the sonata, but also his Nuit Exotique, for violin and piano, plus several works for cello, for string quartet and for orchestra. The year was also marked by the premiere of Bloch’s Baal Shem, a suite of Jewish nature (“Baal Shem Tov” was the honorific name given to the 18th Century founder of Hasidism), performed by the violinist André de Ribaupierre (a student of Ysaÿe, as was the teenage Bloch before the legendary violinist steered him toward composition) and pianist Beryl Rubinstein. The same duo would introduce the Second Violin Sonata almost immediately upon its completion.

Bloch’s First Violin Sonata, dating from 1920, was an anguished response to the recently completed Great War. He also felt that the “peace” that followed was not sincere and was too superficial. The Second Sonata, this “mystical poem,” was written four years later, and functions as a sort of reaction to the First Sonata, and also to the state of the world as he saw it. In Bloch’s words, it portrays “the world as it should be: the world of which we dream,” pictured in “a work of idealism, faith, fervour, hope, where Jewish themes go side by side with the Credo and the Gloria of the Gregorian Chant.”

Written as a single-movement, fantasy-like work, there is a gentle passion, a sense of another, higher reality, to Bloch’s Second Sonata. Its manner of expression is unusually lyrical and seemingly effortless. The sonata is warm and emotional, with elements of simplicity amplified by intervallic uses of fourths and fifths. The music has a spontaneous feel to it, a natural flow.

Bloch’s sonata is a piece that places great technical challenges on a violinist. It demands a constancy of lyricism, of singing and soaring lines that are executed in extremely high registers, therefore in high hand positions, continually unfolding over the long form of one extended movement. The piano part resembles a transcription of an orchestral score, replete with rich sonority and colors. It is very impressionistic writing, requiring a good use of pedal. Largely absent the flash of histrionics, with only hints of the Judaic exoticism that characterizes much of Bloch’s oeuvre, the sonata calls upon an ever-developing, controlled romanticism from its performers, establishing its unique identity through shifting moods of pensive reflection and high-flying ardor.

In the emotional center of the work, Bloch incorporates a Christian element, of the Gregorian chant, Gloria of the Mass Kyrie Fons bonitatis, which is shared between piano and violin, with a traditional Amen played at the end of the section on the violin. Added to the few touches of traditional Jewish musical style, this lends the Second Sonata its own unique universality.

While Ernest Bloch was known to sometimes suffer from serious bouts of depression, his pantheistic sonata closes in a spirit of revelatory joy, its mystical affirmation as moving in the present day as it was in the time between two devastating wars almost a century ago.

Notes © 2012 by Midori, OFFICE GOTO Co.,Ltd.

Referential sources available on request.

JOHANNES BRAHMS: SONATA IN G MAJOR OP. 78

JOHANNES BRAHMS

(born 1833 in Hamburg; died 1897 in Vienna)

Sonata Op. 78 (1878-79)

1. Vivace ma non troppo

2. Adagio

3. Allegro molto moderato

The work of Johannes Brahms epitomizes the central German tradition of the Romantic era. “A genius,” according to Robert Schumann, Brahms’s works combine a classical style with a Romantic temperament. The effects of his sonorities are extremely varied, ranging from a violent symphonic texture to the delicate whisper in a song.

In his personal life, Brahms was stubborn and reserved as well as loyal and generous. His life-long devotion to the Schumann family is well known; although he remained a bachelor, his attachment to Clara Schumann, Robert’s widow, and to their children, was of particular importance to his emotional and musical life.

Brahms composed his Sonata in G Major, Op. 78 shortly after the untimely death of his 24-year-old godson, the violinist and poet Felix Schumann. Although the sonata reflects Brahms’s sadness, the overall effect of the work could be described as tender rather than despondent. Upon receiving the completed manuscript, Clara Schumann is quoted as having said, “[I] could not help bursting into tears of joy over it. … I wish the last movement could accompany me to the next world.”

Written in Portschach in southern Austria in the summers of 1878 and 1879, the Sonata in G Major chronologically follows the Violin Concerto, Op. 77, one of the best-loved works in the violin literature. This sonata is reputed to be the composer’s third or even possibly the fifth attempt at writing a violin sonata. Brahms had written a “Scherzo” movement in 1853, as a birthday tribute to the violinist Joseph Joachim which became a part of the F.A.E. Sonata. This piece was a joint effort with Schumann and Albert Dietrich. Sometime between then and 1878, Brahms tried composing a number of works for violin and piano, but none has survived.

The Sonata in G Major is a three-movement work containing fragmentary references in the first and last movements to two of Brahms’s earlier songs, Regenliedand Nachklang op.59, No.3 and 4, respectively, of 1873. Set to poems by his friend Klaus Groth, they incorporate rain in a symbolic and poetic manner. In the first poem, the rain awakens dreams of childhood, and would “bedew my soul with innocent childish awe” and in the second, raindrops and tears mingle, so that when the sun shines again, “the grass is doubly green: doubly on my cheeks glow my burning tears.” This is not to say that this piece is “program” music; however it gives us possible insight into Brahms’s psyche, as well as that of the performer and the listener, as the piece unfolds.

The first movement opens mezza voce with both instruments playing with a slightly hushed quality. The violin has the main theme, with the memorable repeated “D”s in a dotted rhythm, which begin the melody.

The rhythmic configuration and pattern is quintessentially Brahmsian, especially in the beginning movement. The strong beats of the violin and the piano hardly seem to line up; of course, when they do finally meet, the impact of the emphasis is that much stronger, and the uneven overlapping lines of the two instruments give an incredible sense of a prolonged phrase.

The initial rhythm of the three dotted notes can be heard sporadically throughout the movement, as well as in the middle part of the second movement, marked Adagio. This section is distinguished by the somber quality of a funeral march, in great contrast to the heart-warming sections that precede and follow it.

In the final movement (notice there is no Scherzo in this work, as would have been traditionally expected in the genre), the three “D”s make an appearance again. With the melody that begins with the dotted rhythm, one hears the accompaniment of quiet running 16th notes, from which the Romantic imagination evokes a gentle flow of water, perhaps of rain or of tears.

Later a theme from the second movement returns, suggesting hopefulness, and eventually leading to the triumphant sounds of happiness. The opening melody is heard again, after which the work comes to a quiet end, with a tender reminiscence of the past.

Notes © 2003 by Midori, OFFICE GOTO Co.Ltd.

Referential sources available on request.

JOHANNES BRAHMS: SONATA IN A MAJOR OP. 100

JOHANNES BRAHMS

(born 1833 in Hamburg; died 1897 in Vienna)

Sonata Op. 100 (1886)

1. Allegro amabile

2. Andante tranquillo – Vivace – Andante – Vivace di piu – Andante – Vivace

3. Allegretto grazioso (quasi andante)

Brahms spent the summer of 1886 at his favorite retreat at Lake Thun, near Interlaken in Switzerland. There he concentrated on writing lieder and chamber works, among them his second cello sonata (F Major, Op. 99), the second violin sonata (A Major, Op. 100) and the third piano trio (C minor, Op. 101)

By 1886, Brahms had produced masterworks in every musical genre except for opera. However, his successes had been tempered by the loss of a number of supporters and friends, most prominently Robert Schumann, who died in a mental asylum in 1856, as well as by unrequited romantic liaisons, notably with Schumann’s widow, Clara.

The A Major Sonata is probably the most lyrical of Brahms’s three sonatas for violin and piano. The reigning characteristics of the second violin sonata reflect Brahms’s personality – his shyness and introspection, his originality and his intensity, sometimes all at once. The work transports the listener into the private world of its creator.

The sonata begins with a direct and immediate theme, first presented by the piano and then taken up by the violin. Serving as an antecedent to the dramaturgical line that is to unfold in the rest of the piece, the melody is sweet in its simplicity and powerful in spite of its lack of bombast.

Whereas in the first movement one theme flows directly into the next, and the conversational interchange between the two instruments is intriguing, the second movement can be separated into two alternating sections. Beginning with the bucolic Andante, the folk-like Vivace enjoys a slight hint of humor. The movement ends in a short, light blaze of excitement.

The finale, Allegretto grazioso, is unusual in that it is devoid of the usual bravura excitement in Romantic-period works. The graceful and elegant rondo begins with a soulful line expressed in sustained legato. Mid-movement, there is a rather sudden passionate outburst and emotional upheaval. However, the poignantly calm theme of the opening returns to end the work in an expression of triumphant dignity.

Notes © 2003 by Midori, OFFICE GOTO Co.Ltd.

Referential sources available on request.

JOHANNES BRAHMS: SONATA IN D MINOR OP. 108

JOHANNES BRAHMS

(born 1833 in Hamburg; died 1897 in Vienna)

Sonata No. 3 for Violin and Piano in D minor, Op. 108 (1886-88)

I. Allegro

II. Adagio

III. Un poco presto e con sentimento

IV. Presto agitato

By the time Brahms spent the summers of 1886, 1887, and 1888 at Hofstetten on Lake Thun, he was getting close to his retirement from composing, having successfully established his international reputation with large-scale works, including the four symphonies. Nevertheless, in this idyllic setting, he wrote a large number of lieder and chamber works, including the Sonata Op. 99 for Cello and Piano, and two sonatas for violin and piano, Op. 100 in A Major, and Op. 108 in D minor.

The D minor Sonata is distinctive from Brahms’s two other violin sonatas by virtue of its more extroverted and virtuosic nature. It is almost as though Brahms meant the work to be performed in a larger venue like a concert hall, rather than in a salon-type room, as the term chamber music suggests. The last movement in particular contains large-scale sections that can be characterized as symphonic, and the Sonata certainly needs ample space for the sound to resonate.

Although Brahms’s oeuvre for the violin includes only three sonatas, a single concerto, the scherzo movement from the FAE sonata, and a double concerto for violin and cello, he was certainly familiar with the potential of the violin as a solo instrument through his friendships with the violinists Eduard Remenyi (born Eduard Hoffmann), with whom he toured as a young pianist in 1853, and Josef Joachim, the great violin master and composer.

Both of Brahms’s first two sonatas for violin and piano were written in three movements; however the D minor sonata is in four movements. It opens with a lyrical theme of shimmering beauty played by the violin while the piano accompanies with syncopated rhythm creating a feeling of urgency. The syncopated rhythm or its variant (where the weaker beats are emphasized more than the stronger ones) persists throughout the movement. Also of interest is the development section where the ostinato (a short musical phrase or melody that is repeated over and over, usually at the same pitch—in this case a bass note that is repeated), on the piano continues for a very long time—forty-six bars.

The middle two movements offer great contrasts of tuneful simplicity and nonchalant humor. In the second movement, Adagio, Brahms takes ample time with elegiac pondering. The almost sentimental Scherzo, Un poco presto e con sentimento, follows in duple meter (2/4), rather than the expected, more conventional, triple meter.

The Finale, Presto agitato, offers fire and excitement, and is the most symphonic of all the movements. Syncopations are again a characteristic element. The work builds up to a climactic, if somewhat tragic, ending in the home key of D minor.

During his lifetime, Brahms was greatly respected and admired, although he had his share of detractors, including Wagner, Tchaikovsky, and George Bernard Shaw (in his time a highly regarded music critic), all of whom took exception to his work. However, Brahms also had a dedicated group of followers, who included Robert and Clara Schumann and Hans von Bülow, the conductor and pianist to whom the D minor Sonata was dedicated. The work was premiered in Budapest on 22 December 1888 by the Hungarian violinist Jeno Hubay, with the composer at the piano.

(August 2004)

Notes © 2004 by Midori, OFFICE GOTO Co.Ltd.

Referential sources available on request.

JOHANNES BRAHMS: SONATENSATZ

JOHANNES BRAHMS

(born 1833 in Hamburg; died 1897 in Vienna)

Sonatensatz (1853)

1853 turned out to be a very special year for Johannes Brahms. The young musician, still on the cusp of a remarkable career, was introduced to Clara and Robert Schumann, the musical power couple of their era, by another influential musician, Joseph Joachim. Although Joachim, a virtuoso violinist of Jewish-Hungarian origin, and also a conductor, impresario and composer, was just two years senior to Brahms, he was already solidly established, and his endorsement of Brahms showed great belief in the promise and the future success of the younger musician.

The F-A-E Sonata, from which the Sonatensatz derives, is a collaborative work also dating to 1853, with three composers writing different movements independently of each other. The idea for creating such a piece came from Robert Schumann, the completed sonata to be given as a birthday gift to Joachim. Along with Brahms, who composed the third movement, Schumann took charge of the second and the fourth, while Schumann’s student, Albert Dietrich, got the first. F-A-E is an acronym of a German expression, “Frei aber einsam” (meaning “free but lonely”), an epigram that Joachim had personally embraced — and the dedication of the piece reads (per translation), “F.A.E.: In expectation of the arrival of their revered and beloved friend, Joseph Joachim, this sonata was written by R.S., J.B., A.D.” It was presented to Joachim, who, immediately after playing it through with Clara (a great pianist), was able to correctly guess at the composer of each movement.

Today, the sonata is seldom performed in its entirety. Schumann later in the same year repurposed the movements he contributed to the F-A-E to complete his Sonata No. 3 for Violin and Piano. Brahms’s movement, a scherzo, was only published in 1906, after his death, as a stand-alone work, at the behest of the aging Joachim, who had retained a copy of the entire manuscript. Although the rest of the piece did get printed subsequently, only the Brahms scherzo has become a part of the standard repertoire, as an independent work.